The Name, The Fame, Or Both?

✎﹏﹏﹏﹏﹏﹏﹏﹏﹏﹏﹏﹏﹏﹏

With a 78-year-long reign and hundreds of all-stars, the National Basketball Association has bestowed hundreds of groundbreaking players who help keep old fans and attract new ones. Even with all this talent, there is something that always separates superstars and all-stars: playoff performance. The performance that gets your name known, and more importantly, remembered for centuries. Like the great Walt “Clyde” Frazier has stated, “The regular season is where you make your name, the postseason is where you make your fame.”

This could not be closer to the truth. In some cases, there is much more nuance to this quote. Players like Wilt Chamberlain were only a name for most of their careers until he proved to the world that he could make his fame in 1967 and 1972, respectively. Today, we will dive into the bizarre nature of Wilt Chamberlain’s career and how he has one of the most unique cases regarding this quote. He could dominate statistically, even if it didn’t always translate to postseason success. This begs the question: did Wilt Chamberlain represent more of the name, the fame, or both? What do people remember him for, and why?

•❅──────✧❅✦❅✧──────❅•

The Name: 1962 NBA Season

Let’s take a trip down memory lane, where I discuss with you all the statistical accomplishments of this specific season, 50.4 points, 25.7 rebounds, and 2.4 assists. Just by looking at this, his season should have solidified the title of the greatest season ever, which includes such seasons as ‘62 Bill Russell, ‘13 LeBron James, ‘91 Michael Jordan, and ‘00 Shaquille O’Neal.

If you had no idea what occurred this season, and you just assumed that a player this dominant won the championship, you would believe that this is the greatest peak ever. However, even with these ridiculous numbers, how do people even have the audacity to say that this wasn’t his peak season?

When factoring Wilt’s ability, stats, and the new records, what held ‘62 Chamberlain back from the “greatest season ever” was that his playoff run wasn’t too impressive. It really couldn’t be anything else. He has the signature moment, he created one of the NBA’s greatest memories; his 100 point game versus the Knicks in the regular season. He was the main player in Philadelphia who was very successful record-wise. So his playoff performance is quite easily what holds him back.

Wilt Chamberlain and the Philadelphia Warriors (now the Golden State Warriors) would enter the NBA playoffs with the Syracuse Nationals (now the Philadelphia 76ers) as their head to head matchup. He would dominate the Nationals. He averaged 37 points per game, 27 rebounds per game, and 3 assists per game, on decent efficiency. However, this series still went to the final game. Some argue that Chamberlain could’ve ended the series quicker if he wanted to, but I am here to argue that maybe his stats weren’t as impactful as they were supposed to be.

In the regular season, he averaged 50.4 points per game on 53.6% TS (+5.7 rTS). However, this dipped down to 35.0 points on 50.8% TS (+3.5 rTS). This is concerning because he is not even playing his biggest rival, Bill Russell. In the vacuum, this looks fine, but when you factor in context, he heavily underperformed compared to his regular-season campaign. Not only would Wilt’s historic 1962 campaign end with a whimper but his team success was also non-existent past the 1st round of the playoffs.

I do understand that playing Bill Russell is no small feat, and that most players would scoreless against him. But, there is no excuse for Chamberlain’s scoring average to dip by 15.4 points and his TS% to dip by 2.8%. Chamberlain’s scoring average would dip from 37.0 PPG in the first round of the playoffs to 33.5 PPG in the second round. On top of that, his efficiency would go down slightly as well.

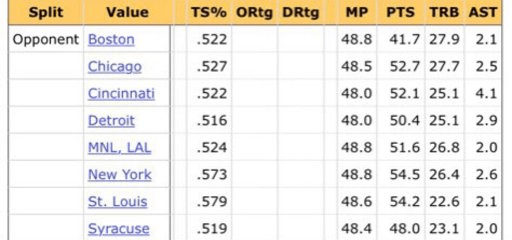

He could do whatever he pleased against other teams, but he struggled mightily against the defensive prowess of Bill Russell and the Celtics. Chamberlain consistently played worse against Boston. As you can see below, his stats lower whenever he faces Boston. He scored the least amount of points on average against Boston.

It’s not all horrible for Wilt Chamberlain. He did have some dominant games versus Boston in 1962 with his most obvious one being his 42 points and 37 rebound performance in a Game 2 victory. However, it was close throughout and the Warriors only squeaked by with a 7 point win. How could this be possible? How could a night like this BARELY get the win? The easy answer is the Celtics were just amazing, they won 60 games in 1962. However, this question needs a lot more analysis than most questions.

✪✪✪✪✪

Wilt’s Obsession

Wilt was a superior athlete compared to the rest of the players in his era. His supposed vertical, speed, and strength were easily translated to the NBA. His insane scoring output generated tremendous amounts of gravity that manipulated the defense. He could do anything you asked of him on the floor. On the other hand, people will say he also had a horrendous lack of a killer instinct. So much so that a rampant narrative made by pundits back in the day was “Wilt was missing the leadership abilities and intangible mental qualities.” It seemed like he was a polarizing player on and off the court because he truly didn’t know what he wanted in not just basketball, but in life. Media members didn’t like his apparent stat-padding and playoff losses.

Needless to say, Wilt “The Stilt” Chamberlain cared too much about his stats early in his career and it was obvious. Sports Illustrated highlighted in their March 11th, 1968 issue that “Wilt Chamberlain is leading the league in complaining about statistics.” This is something that held people back from saying Wilt was “ the best player in this season.” before 1967. Certain fans may undermine Bill Russell’s greatness because Wilt Chamberlain had more eye-popping stats, but they don’t comprehend that the byproduct of Chamberlain’s lack of team success before 1967 was his obsession with statistical feats and records.

From checking the stat sheet during the game and correcting the points he scored, to simply sometimes not trusting his teammates enough is ultimately what held back the Warriors, 76ers, and Lakers from winning more championships than they did. Although it is very fascinating to realize that Chamberlain could put up whatever stat whenever he wanted, and it didn’t help his team overachieve. In some cases, they even underachieved. Chamberlain needed to start winning soon or else he would just be another great player with no championships. He needed the secret to winning. This brings us to the next section.

•❅──────✧❅✦❅✧──────❅•

Side Quest: Why “Wilt Ball” Never Worked

You may be wondering why this “Wilt ball” never proved to work. I mean after all, 50 points per game SHOULD be valued the same wether or not it’s all coming from one player, right? Well, in a vacuum, you may be right but that’s not what the rule of Global Offense would tell you.

Global Offense: The idea that the league’s shift toward a team-oriented, highly fluid offensive strategy is more impenetrable than a traditional, heliocentric offensive system. This approach emphasizes constant motion, passing, and player movement, one that you’d see in a team like the 2014 San Antonio Spurs rather than relying on a single dominant player creating plays in isolation, like the 2025 Oklahoma City Thunder.

It’s safe to say that in 1965-66, the year before the 76ers won their Wilt-era championship, they were more akin to a stagnant, predictable 2025 Thunder offense, than the potent, creative 2014 Spurs. Wilt attempted roughly 25 shots per game, (leading the league), and back in the day, teams believed the myth that this was good offense. After all, he was his team’s most efficient scorer and fittingly, he shot the ball the most. A team should want its most efficient scorer to shoot constantly, or so they thought.

In his 2016 book aptly titled “Thinking Basketball”, Ben Taylor references the “traffic paradox” which debuted in a 2010 article written by Ben Skinner. I loved this analogy so much that I thought I’d explain it here to help elaborate on the sometimes, confusing downsides of one player shooting too frequently. Overall, much in the same vein of automobile drivers taking different routes home via highways, local roads, etc. In one scoring “path”, a point guard might hoist up a jump shot, or a center may get fed the ball constantly, or there could be a diverse array of “paths” used to score.

In the book, Taylor states “In Chamberlain’s case, his “scoring attempts” – any field goal attempt or two-shot free throw attempt – represented one possible path for his team to score.’ In 1966, he converted those paths at about 1.09 points per attempt, well above the league average of 0.97. But Philadelphia took other paths to score as well. Sometimes, Chamberlain twisted, turned and dished off to a teammate. Sometimes, he never touched the ball at all. On all of the paths that did not end with a Wilt Chamberlain attempt, the 76ers scored at a rate of 0.94 points per attempt.”

Now, you may be thinking that the math ain’t mathing here, and from a surface level perspective you would be right. Crazily enough, despite the fact that Wilt was dominating the touches over his below average efficiency teammates, his teammates, and the 76ers as a whole, became much more efficient when Wilt decided to shoot less!

This relates to Braess’s Paradox, the idea that if each driver is making the optimal self-interested decision as to which route is quickest, a shortcut could be chosen too often for drivers to have the shortest travel times possible. In simpler terms, Braess’ discovery is that constantly depending on the best option may not always equate with the best overall flow through a network. The 76ers were using Wilt as their “best option” but the overeliance on his production caused a basketball-themed traffic jam and it is overall, the main reason why “Wilt Ball” never worked.

The 76ers began emphasizing a Global Offense, one where Wilt took exactly 11 less field goal attempts per game but as a result, Billy Cunningham, Chet Walker and many other role players saw leaps in their production and efficiency as Chamberlain cruised to a then-career-high in assists at 7.8 a contest.

You can see below the Power Plays that Philly would execute in the half-court, such as punishing defenses for drawing multiple defenders at Wilt, or fastbreak plays that punished a slow pace, or overcommitment to one transition threat. This contributed to a dominant, consistent stream that the Sixers fell back on for easy buckets.

•❅──────✧❅✦❅✧──────❅•

Power Play: An offensive strategy designed to create a momentary, unbalanced advantage by drawing one or more defenders to a single player.

•❅──────✧❅✦❅✧──────❅•

The Fame: 1967 NBA Season

What isn’t there to say about Wilt Chamberlain’s 1967 NBA Season? He did everything that the media members said he couldn’t. Thus, getting everyone who hated his playstyle to love it. The Big Dipper finally realized what it took to win.

Since the media kept harassing Chamberlain for losing a lot in the playoffs, he started trying techniques to help his stats look better so he could take less of the blame. When he developed his reputation of a loser who couldn’t get over the hump, he scored more points and grabbed more rebounds, to get more people to defend his losses. Then he became known as more of a “selfish player”. Therefore, he started to force passes whether or not he got an assist. Then people started to complain about his “stat-obsession” or his “harmful ego”.

In some cases they are correct, Chamberlain tried too hard to please everyone and that could have been the reason he didn’t win as much as other league legends. However, in this particular season, Chamberlain realized that in order to truly shave off all the critics he had to make winning a priority. He stopped forcing shots and rebounds and other stats and started playing in the flow of the offense. He started taking what the defense was giving him, and THAT is what won Chamberlain the elusive title that he always wanted and needed.

✪✪✪✪✪

Coaching Matters

![The Name, The Fame, Or Both?-[C]✪✪✪✪✪

[BCI]Introduction

[IMG=B4L]

With a 75 year-long reign and hundreds of all-stars, the Na](https://pm1.aminoapps.com/7745/62ecc06b014017c4dd5952ae1bfe6fb129d8f9d2r1-720-480v2_hq.jpg)

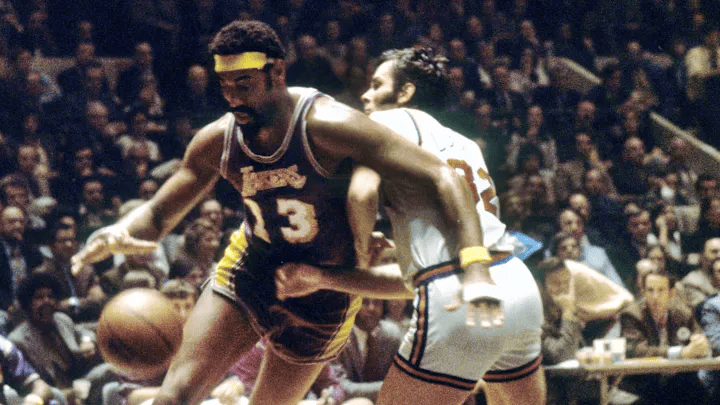

’67 Wilt Chamberlain

- 24.1 PPG

- 24.2 RPG

- 7.8 APG

- 63.7 TS% (+14.4 rTS)

Part of the reason Chamberlain and his team were pushed to brand new heights was because of the new coach hiring. The 76ers hired Alex Hannum and he soon started to whip Chamberlain into shape and started to change the team’s culture and play so that Philadelphia could start winning games. As a result of this, Chamberlain no longer believed in the philosophy of hero-ball. When he played hero-ball, he usually lost. However, when he didn’t, his team had a massive improvement as they started the season on a RIDICULOUS 46-4 record. Soon after, he would win the finals against his former team in 6 games.

Chamberlain didn’t change what he could do, he changed the way he played, he averaged the lowest point total of his career and the Sixers ended up with a 68-14 record. Changing the detrimental aspects of your game is extremely difficult, but Wilt did it! This is what players such as Russell Westbrook have struggled to do over the course of about 13 seasons.

One quote that sums up this specific season miraculously is from Chuck Closterman in the “Book Of Basketball” Written by Bill Simmons. He highlights “Bill Russell possessed intangible greatness. Which means that sportswriters can make him into any metaphor they desire, Russell was the central figure for a superior franchise so his history suggests he was the more meaningful force, his winning validated everything. If you side of Chamberlain, it seems like you are siding with the absurdity of numbers. I pose you this question, with a different attitude could Chamberlain have been Russell? Probably.”

The 1967 Eastern Conference Finals is a great representation of the potential value Wilt Chamberlain possessed in every game he played. He was facing a 60 win Celtics team, with a unanimous top 5 player EVER. If the Celtics win, they win seven straight finals. This was a different Wilt Chamberlain, he didn’t try to carry his team to victory by chucking up shots, he finally trusted his teammates to be involved, and he fell into the flow of the offense like never before. He would finally ignite a belief amongst his teammates that they could end the series in a victorious fashion.

During Game 1 in Philadelphia, Chamberlain grabbed a historic 32 rebounds, and Hal Greer would follow it up with 39 points to help defeat the Celtics and set the tone of this series. Wali Jones, Billy Cunningham, and Chet Walker, are the other 76ers that scored double digits.

Now in Game 3, where the pressure is on as the Sixers are on Boston’s home floor. Wilt would be the driving force of a 3rd straight Sixers victory as he scores 20 points, pounded the glass with 41 rebounds, and even dished out 9 assists. The momentum of this rivalry took a sharp turn.

Game 5 had greatness written all over it, the momentum palpably shifted in favor of Philadelphia and Convention Hall had legacy bursting at it’s seams; it happened. The Sixers did the unthinkable against a heavily favored Celtics team. This Philadelphia win got them their first finals appearance in 12 seasons. This was the biggest mountain any player had to climb, and Chamberlain did it.

The Stilt was a heavily anticipated prospect in the late 50s and was 48 minutes away from bringing his hometown city a conference championship against one of the greatest teams ever, with some of the greatest players ever, he finally played up to his talent and overcame the Boston-sized hump. After breaking his team’s heart for 7 straight seasons, he would go on to defeat Rick Barry and his former team, the San Fransisco Warriors in six games to finally deliver himself a championship.

✪✪✪✪✪

Essence: What does Wilt represent?

![The Name, The Fame, Or Both?-[C]✪✪✪✪✪

[BCI]Introduction

[IMG=B4L]

With a 75 year-long reign and hundreds of all-stars, the Na](https://pm1.aminoapps.com/7745/3553a39f17e951afbe985c888d4304e0017479f0r1-1920-1080v2_hq.jpg)

Now for the moment of truth, the question that I posed at the start of the article. In my opinion, Wilt Chamberlain represented both the name and the fame equally. My reasoning behind this is because Chamberlain’s career felt like multiple, he had really high moments and really low moments. Due to this, he is extremely difficult to rank he could be in many different spots amongst someone’s 10 greatest.

For the other question, it depends. The side of fans that thinks winning is above all else will probably remember Chamberlain more for the name since he choked a lot throughout his career, 1962 being a good example of this. On the other hand, the side of fans that love box score numbers and believe that Chamberlain needed a good coach to succeed, will probably remember him more for the fame. This is because Chamberlain was extremely successful under coaches such as Alex Hannum, 1967 is also a good example of this. This demonstrates why many fans just like you and I are extremely infatuated with Chamberlain’s career.

Wilt Chamberlain isn’t Bill Russell, don’t expect him to be. He’s not Michael Jordan either, he’s not LeBron James, Shaquille O’Neal, or Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. He is Wilt Chamberlain; a gifted player who was a spectacle to watch, the greatest statistical player ever and because of his fluctuating team success he is also the most polarizing player ever. His careers are split into two, one half representing the name and the other representing the fame, a true commodity.